The Best Baseball Game this Year

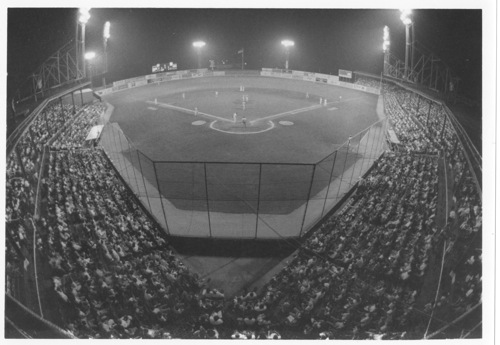

In 1991, Chicago's Comiskey Park became a parking lot (for the new Comiskey Park). Thus Birmingham, Alabama's Rickwood Field, which turns 104 this season, earned the distinction of America's Oldest Professional Baseball Stadium. The home of both Birmingham's Barons and the Black Barons of the Negro Leagues had essentially stood empty since the Barons (now a White Sox double-A affiliate) moved to the suburbs in 1987. And the wrecking ball loomed.

Enter a group of young Birmingham professionals who might have gotten together for bowling or pizza. But they cherished childhood memories of storybook sunny days spent in Rickwood's grandstand, rooting for the home team.

Moreover, they viewed Rickwood as a treasure. You could step into the park, they felt, and, without trying, practically channel the 10,000 Coal Barons boosters who overflowed the stands on Opening Day in 1910. You could breathe a bouquet of talc, freshly-poured Stroh's beer, and broiling woolen suits. You could hear the hurrahs -- you might even catch a suggestion that the umpire have his spectacles checked. A resounding crack of the bat was almost a certainty. Then you kept an eye cocked, half-expecting a Ty Cobb to charge, like a locomotive, after a fly ball.

Cobb played at Rickwood, as did Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. Satchell Paige graced the mound. Willie Mays began his career as a Black Baron. As an Oakland (then Kansas City) A's minor leaguer posted to Birmingham, Reggie Jackson belted balls, it seemed, to Oakland. And on barnstorming tours or stopovers to and from spring training, many more Hall of the Famers dug spikes into Rickwood's diamond.

Lynryrd Skynrd played there, too -- a concert in 1974 included the group's new song, Sweet Home Alabama. Baseball was just part of Rickwood's history. Alabama and Auburn's football squads used to meet on Rickwood's gridiron. Chapters of the Civil Rights story took place at the park as well: It was singular as a venue for civic pride, both black and white.

"We couldn't let something as beautiful and significant to our city as Rickwood be torn down," said Tom Cosby. In 1991, Cosby was a vice president at the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce. He joined the group of young professionals who set about restoring Rickwood to its heyday.

The first step was getting into the park. It was locked.

The group went to City Hall and pleaded to Mayor Richard Arrington that Rickwood was "a national treasure that wasn't just unique in baseball, but unique in general." They came away with a 99-year lease at one dollar per year.

Some people considered it a lousy deal.

The roof was caving in, the grandstand was crumbling, and the field looked like it had hosted a war. Also the locker rooms were furnished to the tastes of the disco era, and dilapidated. Similarly, many of the vintage wooden seats -- imported from the Polo Grounds when that historic ballpark was razed -- had been discarded and replaced with garish ("interstate highway orange," as Cosby puts it) plastic ones, which birds had been using as restrooms for years.

Cosby's group, the non-profit Friends of Rickwood, rolled up their sleeves and fixed and scrubbed whatever they could, possibly putting more sweat into the park than any team that played there. With $2 million they raised, they also restored the stadium's majestic, spearmint-green facade, rebuilt the grandstand roof in painstaking period detail, revitalized the hand-operated scoreboard, constructed a new (though antique in feel) press box, and installed memorabilia displays. Then they opened to visitors.

In 1993, Rickwood Field was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Warner Brothers selected it as a principal location for the movie Cobb. And USA Today listed it among its "10 Great Places for a Baseball Pilgrimage."

In 2004, during his first visit in forty years, Willie Mays stepped to the plate, looked the park over and remarked that it hadn't changed. Which perhaps best summed up the Friends of Rickwood's accomplishment.

But their job had barely begun.

"The challenge is that of an old house, on the grandest scale," says David Brewer, the Friends' Executive Director.

Contributions from the city, along with field rental fees for the 80 or so high school and college games played at Rickwood each season, constitute the bulk of the park's annual $150,000 budget. Which hardly covers the maintenance. According to another of the volunteers, "It's mostly done with shoestrings and gum and chicken wire."

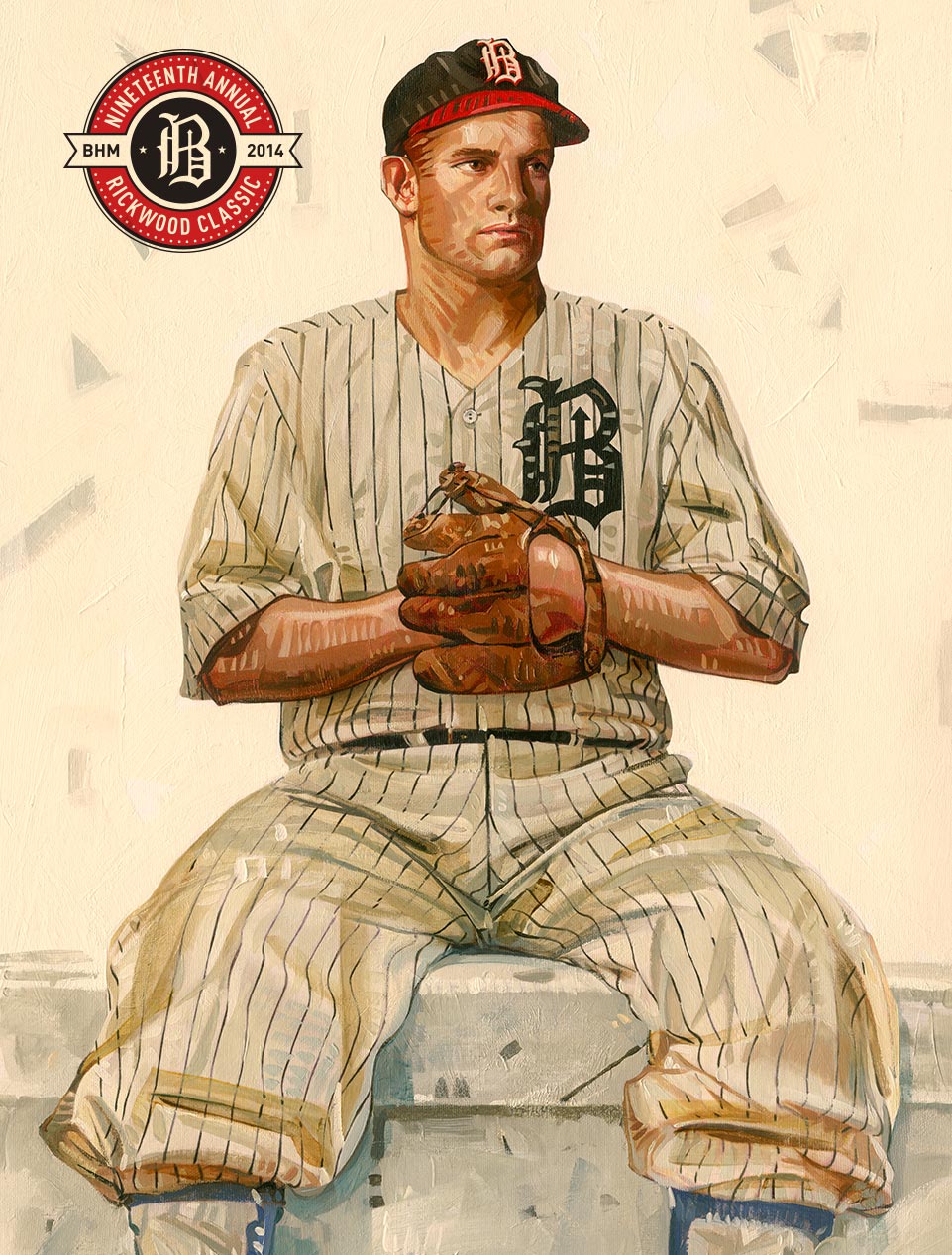

One of Rickwood's greatest benefactors is its ex-tenant. For fourteen years, the Barons have played one game per season at Rickwood. The 6,500 tickets sold on average have provided a huge boon to Rickwood. And the "Rickwood Classic" is no mere game. Watch players bound onto the field in flannel uniforms, hear jazz piped through the funnel-shaped speakers, lick a snowcone, and good luck convincing yourself that, on the way from the parking lot, you did not pass through a wormhole in time to 1910.

ESPN recently ranked the Rickwood Classic among "101 Things All Sports Fans Must Experience Before They Die."

The 2014 Rickwood Classic, pitting the Barons and Mississippi Braves, will be played on Wednesday, June 25, at 12:30. Tickets are still available. I got your snowcone.